Why hydrogen sensors?

Hydrogen is projected to be omnipresent in the future. Besides being a medium to store renewable produced electricity from intermittent sources such as solar and wind, it has applications in H2-powered heavy-duty vehicles, ships and airplanes, infrastructures, domestic heating, gas turbines and steel production. Also today hydrogen is an important feedstock to the (chemical) industry and used in the production of for example fertilizer.

At any place where hydrogen is used, transported or produced, hydrogen sensors are needed. This is as hydrogen-air mixtures can be flammable or even explosive if the hydrogen concentration in air exceeds 4%. As such, it is of utmost importance to detect hydrogen leakages at a very early stage. In fact, safety is just one reason to produce optical hydrogen sensors. Hydrogen itself is also an indirect greenhouse gas with a global warming potential that is roughly 10 times larger than CO2. Indeed, it prolongs the lifetime of other greenhouse gasses such as methane (CH4). Therefore, it is also essential to detect hydrogen leakages where the concentration may be very small. Furthermore, hydrogen sensors can also be used for performance optimization and predictive maintenance. For example, it could drive the cost of operating electrolyzers (converting electricity to hydrogen) and fuel cells (converting hydrogen to electricity) at a lower cost and higher efficiency.

Why optical hydrogen sensors?

At present, commercially available hydrogen sensors rely either on a catalytic (combustion), electrochemical or thermal conductivity-based measurement principles. While these sensors function for some applications, there are some drawbacks: They feature typically a long response time, low selectivity. Moreover, electrochemical and catalytic sensors require the presence of oxygen to operate and also have a limited lifetime as their performance degrades steadily over time due to consumption of active material, while thermal conductivity based sensors are highly influenced by the temperature, pressure and flow in which they are operated in.

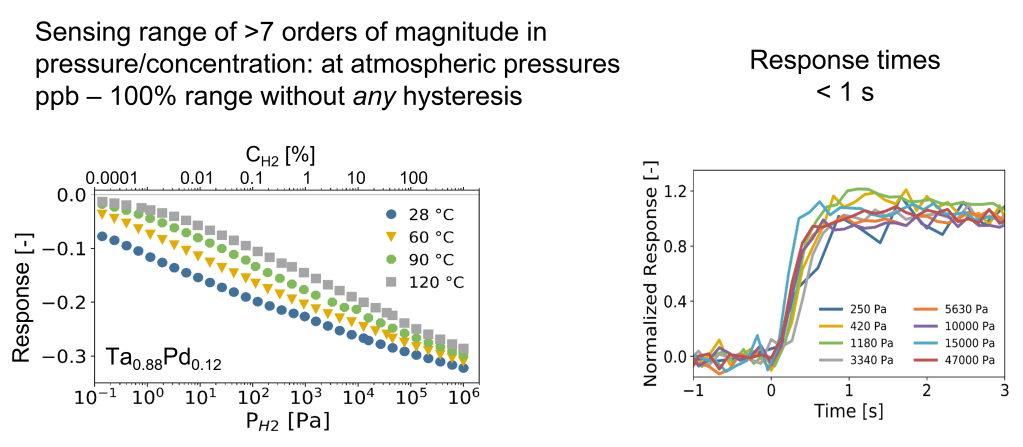

Metal-hydride based optical hydrogen sensors can provide an alternative for many applications. They have the potential to be made cheap, operate without the presence of hydrogen, sense a very larger range of hydrogen concentrations/pressures (low to high) with a high resolution, operate under a larger temperature window and with a fast response. Furthermore, they are intrinsically safe as the read-out is purely optical without any optical sparks. For example, the tantalum-based optical hydrogen sensor developed and patented by TU Delft have, measured in an environment of hydrogen with an inert gas, a sub-second response that is completely free of any hysteresis across over 7 orders of magnitude in partial hydrogen pressure/concentration.

Working principle

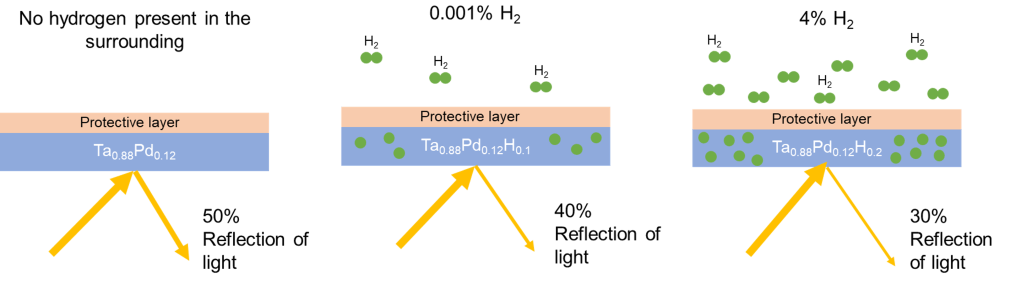

Metal-hydride based optical hydrogen sensors rely on a thin layer (10-100 nm) of a metal hydride sensing material that absorbs hydrogen when there is hydrogen present in the environment of the metal hydride sensing material. In turn, this changes the optical properties of the sensing material. These optical sensing properties can for instance be measured by measuring the reflection or transmission of the material.

Sensing Materials

The core of the optical hydrogen sensor is a sensing material. The properties of the sensing material directly influence the properties of the hydrogen sensor. Indeed, to realise an extensive and hysteresis-free sensing range, the metal hydride should gradually absorb hydrogen upon increasing partial hydrogen pressure/concentration without undergoing a phase transition (i.e., a large solid solution range of hydrogen and the host metal). Plastic deformation is another origin of hysteresis that should be minimized or excluded, implying that the expansion of the material upon hydrogen absorption should be completely elastic. A high sensitivity, i.e. that is a high resolution of the hydrogen sensor, can be achieved by materials that absorb vast amounts of hydrogen and where large changes of the optical properties are induced when hydrogen is absorbed. Differently, to achieve short response times, materials with a high hydrogen diffusion coefficient and that absorb small quantities of hydrogen are optimal, while a stable hydrogen sensor can be achieved by selecting a material that only mildly expands upon hydrogen absorption, does not undergo any phase transition upon hydrogenation, and consists of a single phase. In our group we work on finding those ideal hydrogen sensing materials. We often use the fact that materials, when structured on the nanometer level as a particle or thin film, behave different from a bulk material.

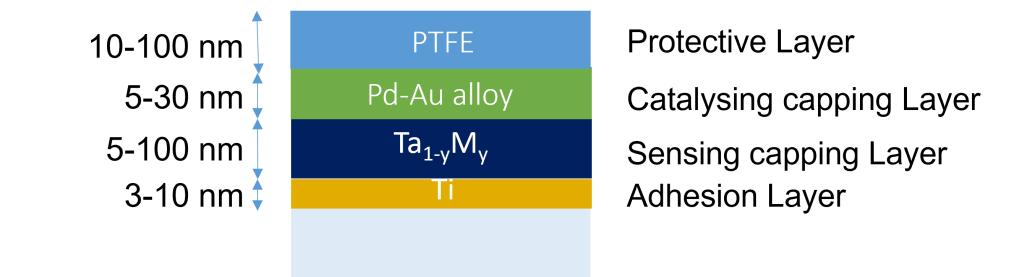

One example of a hydrogen sensing material is the tantalum-based optical hydrogen sensor developed and patented by TU Delft have, measured in an environment of hydrogen with an inert gas, a sub-second response that is completely free of any hysteresis across over 7 orders of magnitude in partial hydrogen pressure/concentration. This material is combined with a thin (5-30 nm) layer of a Pd-Au alloy to protect it against oxidation. Most importantly, this layer also catalyses the hydrogen dissociation reaction: in the environment, hydrogen is a diatomic molecule (H2), while in the material the hydrogen are individual atoms. The Pd-Au catalytic layer catalyses the dissociation of molecular in atomic hydrogen.

Protective coatings

To ensure that optical hydrogen sensing materials can work well in all kinds of environments, protective coatings are needed. While the material is intrinsically very selective to hydrogen, the presence of other gasses can completely kill the dissociation/absorption of hydrogen. To prevent that, we develop coatings that protect our hydrogen sensors and can in some cases also accelerate the response of the hydrogen sensor.

Read-out

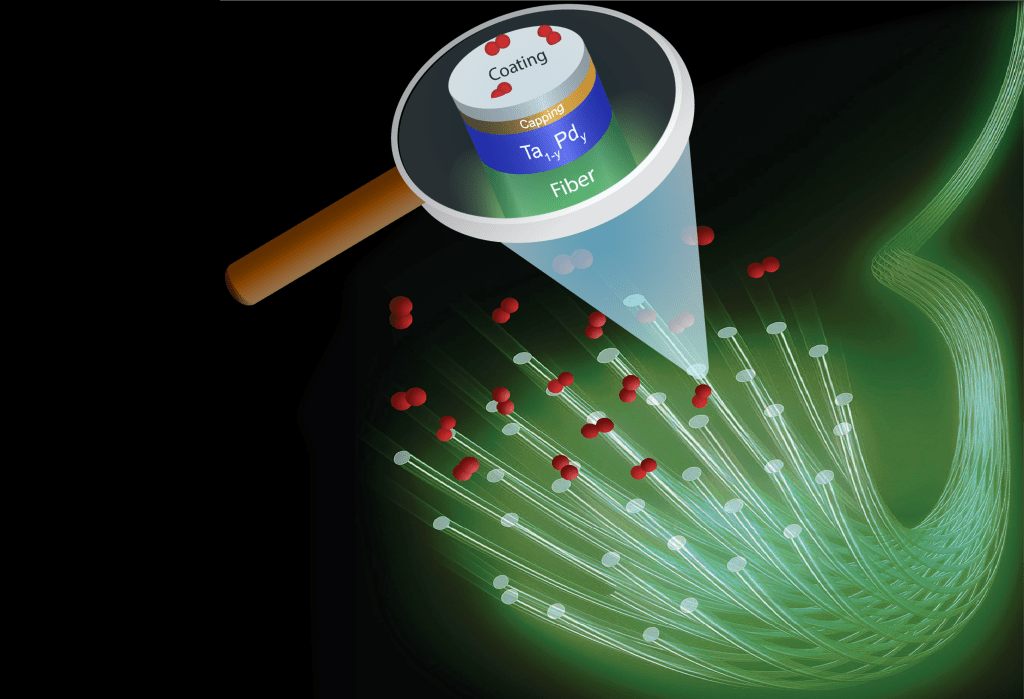

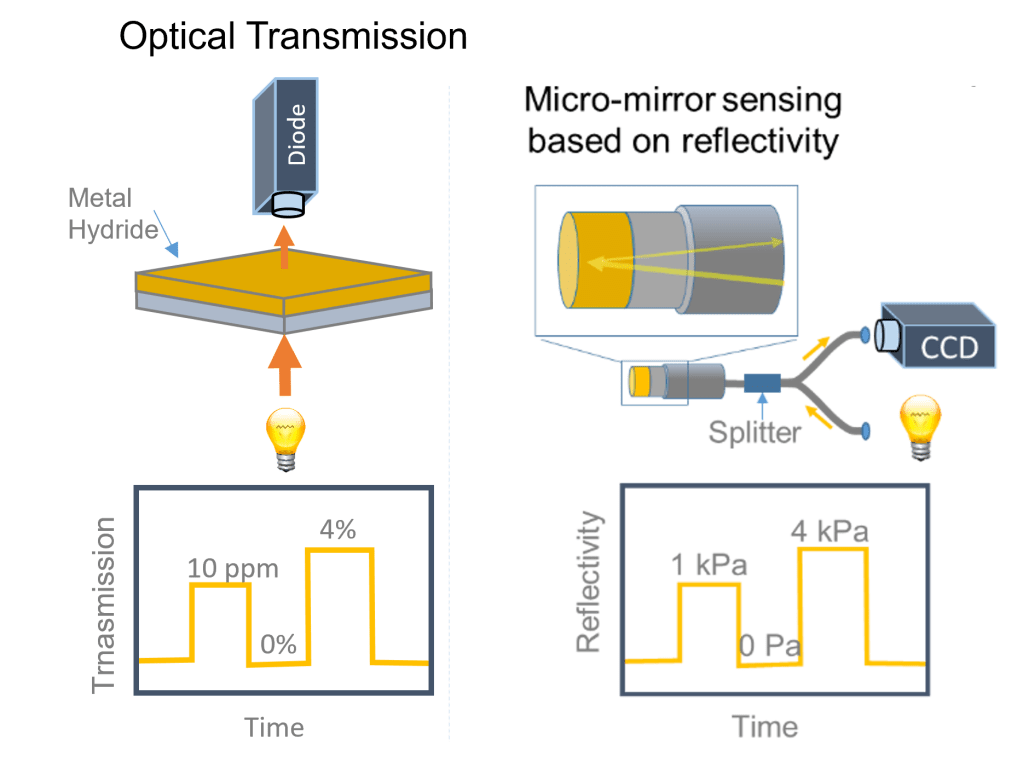

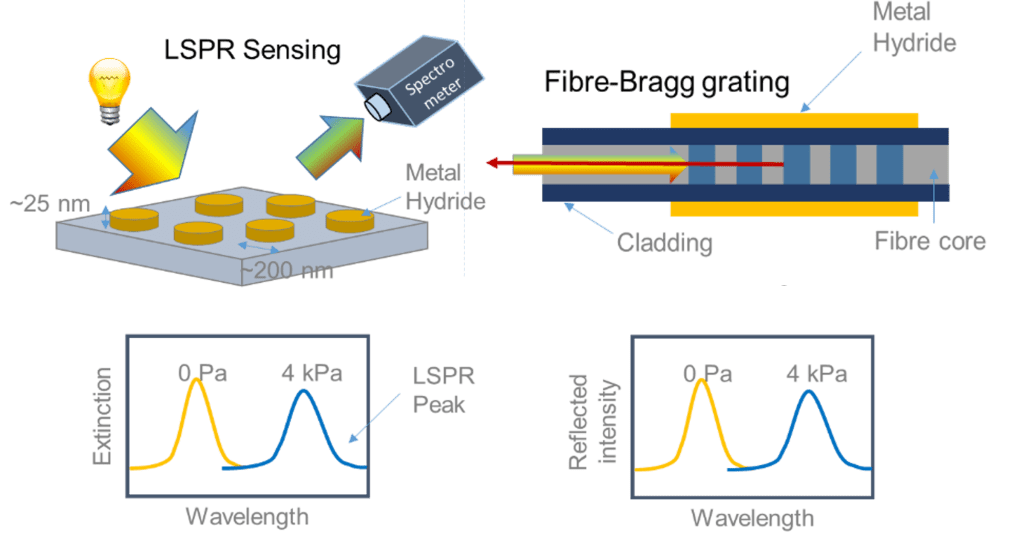

Materials alone do not make a sensor, and an optical read-out system is therefore also crucial to make a hydrogen sensor work. The most simple way to create an optical hydrogen sensor is to simply measure the change in optical transmission of the material when it is exposed to hydrogen. Another method is to measure the change in reflectivity. This can for example be done in a micro-mirror configuration, where the coating is applied on the tip of an optical fibre. Light, which is then coupled into the optical fibre is then partially reflected by this coating and detected by a detector. When hydrogen is present near the tip of the optical fibre, the reflectivity of the coating changes which can then be detected.

An alternative to these intensity-modulated sensors are frequency-modulated hydrogen sensors. One way of doing this is a fibre-Bragg grating. In such a grating, a grating of materials with different indexes of refraction is introduced in an optical fibre. This grating is subsequently coated with an sensing material. When the sensing material is exposed to hydrogen, the wavelength that is reflected by the grating changed, which can be used to determine the hydrogen concentration. Another frequency-modulated hydrogen sensor is based on (localized) surface plasmon resonances. It is based on the principle that when the sensing material is illuminated by light, extinction may occur when the frequency(wavelength) of the light matches the one of the plasmon resonance. When exposed to hydrogen, the plasmon resonance peak position is changed, which can then be used track the hydrogen concentration.

Our research

Our efforts in the field of optical hydrogen sensing concentrate on the following aspects:

- Design new hydrogen sensing materials without any hysteresis, high sensitive, fast response time and a hydrogen concentration range in which the material is sensitive to hydrogen that can be tuned according to the application.

- Develop new read-out methods for optical hydrogen sensors based on optics.

- Develop materials to allow optical hydrogen sensors to work under a variety of environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, presence of other chemicals etc.)